I remember the first time I heard a rain-soaked tale on a dark lane, an old woman pausing to warn me of a hidden spring. That night I began mapping a world where myth and daily life braided together.

In this guide I trace how these stories moved by word of mouth until collectors like Joan Amades wrote them down in the late 19th century. I draw on the Costumari Català and modern commentary to show how origin myths, ritual uses, and local voices shaped what endured.

I treat the material as a living body: motifs repeat across valleys and coasts, yet each teller shifts tone. I explain why legends matter — they give people language for the unexplainable and a way to mark seasons and protect homes.

Expect a clear roadmap: sources, iconic tales, emblematic sites, and the way storytellers adapted materials over time. I respect variation without forcing a single correct version, so you see both function and craft in these traditions.

Key Takeaways

- I ground this guide in field collections like Joan Amades’ work and contemporary analysis.

- Legends are treated as a living tradition that shifts with each teller and place.

- Stories reveal how people name origin forces and shape communal values.

- You’ll get a tour of sources, key tales, and the rituals that anchor them.

- I balance documented texts with performance-based retellings and local voices.

What I Mean by Catalonia Folklore and Why It Matters

I grew up hearing how certain stones and streams carried names, warnings, and bargains from older days. That sense of place shaped how I define this shared cultural world.

Folklore here means the community’s living story-world: songs, sayings, and cycles that survive because people tell them across times and day-to-day life.

Living traditions: beings and elements across land, mountain, and sea

I watch how devils, nymphs, witches, and shape-shifters attach to a ravine, bridge, or peak. Those beings give the uncanny a local address.

Elements — water, fire, air, earth — anchor meaning. A storm becomes a sign; a spring becomes a doorway. These motifs shape choices and safety in daily life.

From word of mouth to the page: how legends traveled through time

Most legends moved by voice until collectors like Joan Amades began writing them down in the late 1800s. Víctor Borràs reminds me that many tales answer a human need to explain origin and hazard.

- Oral exchange keeps a story adaptive and social.

- Writing preserves reach but can flatten performance and gesture.

- Variation shows vitality, not error; local accents matter.

Origins and Keepers of the Myths: How I Trace the Roots

I track stories from hearth to archive to find how they survived change.

Joan Amades and the Costumari Català: documenting customs and legends

Joan Amades collected countless local accounts and put them in the Costumari Català. His work moved many anonymous tales into named records. That move preserved seasonal customs and fixed cycles in print.

Medieval to modern times: why legends of night, day, and “one day” moments endure

Many motifs began in medieval Europe and reappeared across later centuries. Víctor Borràs argues that these narratives answer deep human questions about beginnings and danger.

“Legends respond to human needs to explain beginnings.”

— Víctor Borràs

I weigh the role of recorders carefully. Collectors rescued fragile materials but also shaped which versions became canonical.

| Period | Source | Role of People | Common Motifs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medieval | Oral tradition | Farmers, priests | Punishment, vows, thresholds |

| 17th–19th c. | Local variants | Rural performers | Bargains, night bridges |

| Late 1800s | Collectors/archives | Urban recorders | Standardized texts, rescued tales |

I cross-check versions and honor performance nuances I cannot fully capture on the page. That method keeps the material alive while studying its origin, tradition, and ongoing practice through times.

Iconic Legends I Revisit: Bridges, Knights, and Fiery Eyes

At dusk I often spot where a story began: a bridge, a ruined wall, a hoofprint in the ground.

The Devil’s Bridge is a perfect example of how a bargain at night becomes a way to explain a stubborn crossing. In Martorell a medieval tale recorded by Amades says a devil builds the span overnight for a soul. The trick—sending a cat first or using a rooster to fake dawn—lets humans reclaim agency.

The same pattern crops up in Tarragona, Cardona, and Pineda de Mar. Local pride clings to the stones while the core legend explains why a bridge stands where water once barred the way.

Comte Arnau and the Burning Gaze

I read Comte Arnau as a cautionary tale about greed and broken vows. He is forced to ride forever, a horse carrying him through day and night.

Flames issue from his eyes, mouth, and nose—fire that makes his guilt visible. The image ties punishment to sight: the wrongdoer cannot hide.

Cocollana: Transformation Between Light and Dark

Cocollana began as a nun and, by a strange mercy, becomes a scaled, winged being. Her change happens in the ground-level dark; scales form where light cannot reach.

Her wings suggest residual sanctity—light and shadow in one body. That blend of mercy and curse makes her both monstrous and mournful.

“One small detail in a tale—the first life to cross a bridge, a rooster’s crow—can change the way a whole community reads a story.”

- Pattern: bargains at night, last-moment tricks.

- Reach: variants travel from town to town across mountain passes.

- Meaning: fire in the eyes marks remembered injustice and visible guilt.

| Figure | Core Motif | Lesson |

|---|---|---|

| Devil’s Bridge | Bargain at night; trick reclaims soul | Wit defeats impossible debt |

| Comte Arnau | Eternal ride; flames from eyes | Abuse of power remembered by the land |

| Cocollana | Nun to winged, scaled being | Punishment tempered by sanctity |

Catalonia Folklore: Water Nymphs, Witches, and Elemental Beings

On a moonlit bend of Gualba Creek I once watched a pool keep its own silence while a woman stepped from the water.

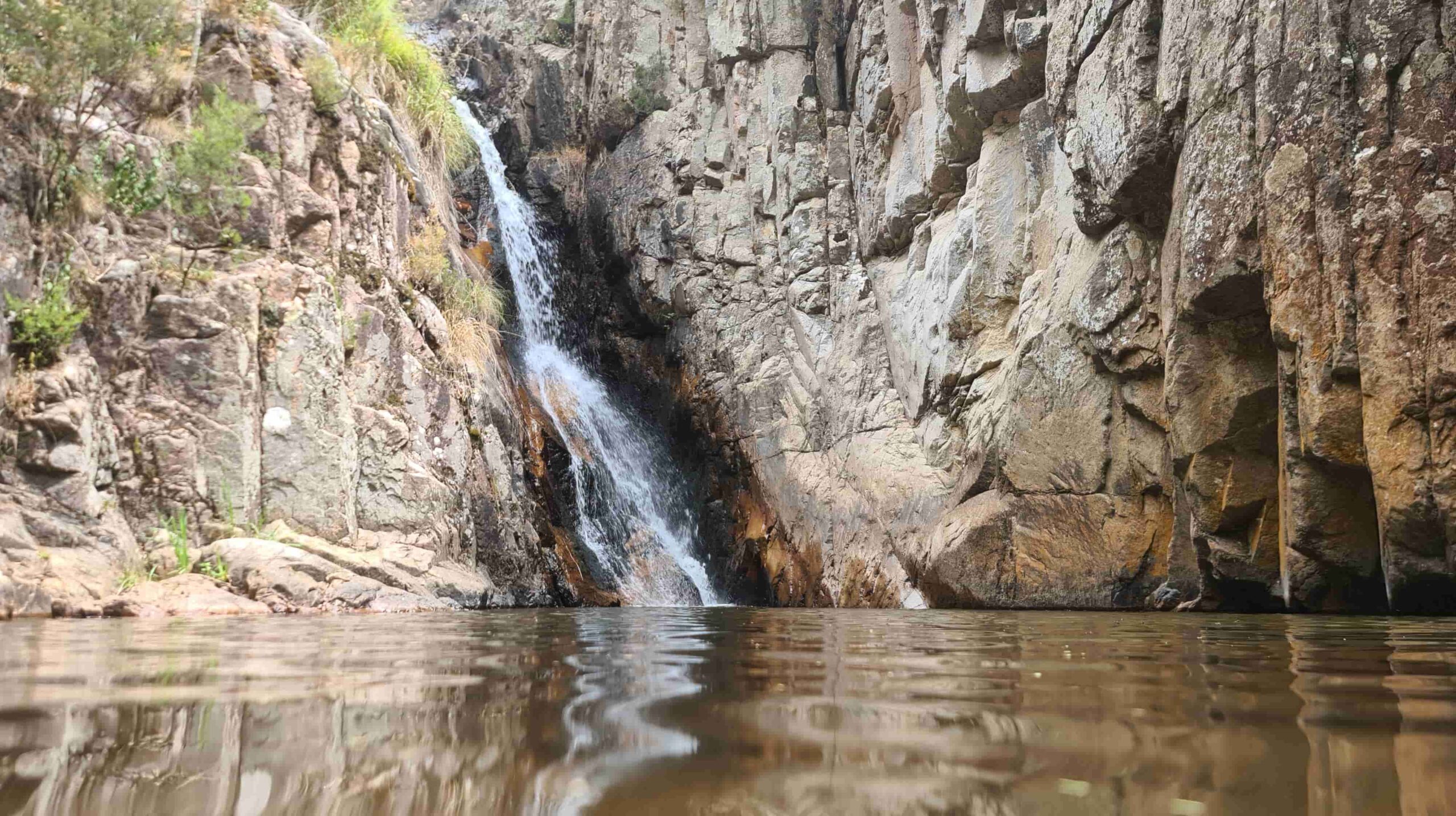

Women of water appear as wise, tender, and dangerous. At Montseny’s Gorg Negre a man met such a woman combing her hair and agreed to marry her. Her condition was simple: he must never raise his voice or remind her origin. One day he broke the oath in a fight about crops, and she vanished into the pool. She later returned by night to kiss their children and left small pearls on the table.

Women of Water: love and oaths at Gorg Negre

The household they built balanced land and water. The woman’s insight guarded the fields. Their daughter and son grew with unusual eyes and a quiet sense of other beings.

Witches and combs: storms, sleep, and strange marks

Tellings mark some witches with a Devil’s bite and odd pupils. Combing hair by a pool, often with a golden comb, links desire to storms. A comb prick will send a girl to sleep in one tale; a thrown comb can raise a forest or flames in another.

Elemental guardians: gnomes, sylphs, salamanders

I place women of water alongside gnomes (earth), sylphs (air), and salamanders (fire). These elements shape how tellers name duties and dangers in the unseen ecology of the world.

“A promise kept keeps two lives; a voice raised sends one back to the water.”

| Figure | Core Trait | Lesson |

|---|---|---|

| Woman of Water | Moonlit pool; oath-bound | Respect binds worlds |

| Witch by the Pool | Combs hair; strange pupils | Beauty and danger linked |

| Elemental Guardian | Gnome/sylph/salamander | Elements order life |

Places, Rituals, and Symbols I Watch For in the Stories

I walk paths and check small marks left by people who once guarded doors and fields. A burned patch, a palm frond over a chimney, or a sprig of rosemary tells me what a community uses to keep watch.

Mountains and ravines: Montseny, Pedraforca, Montserrat

I map high places—Montseny’s slopes, Pedraforca’s fork, Montserrat’s serrated ridge—because a mountain frames where beings meet mortals and the land keeps memory.

At Pedraforca and the Plain of Beret, tellers place gatherings and describe a thickening presence during a single night.

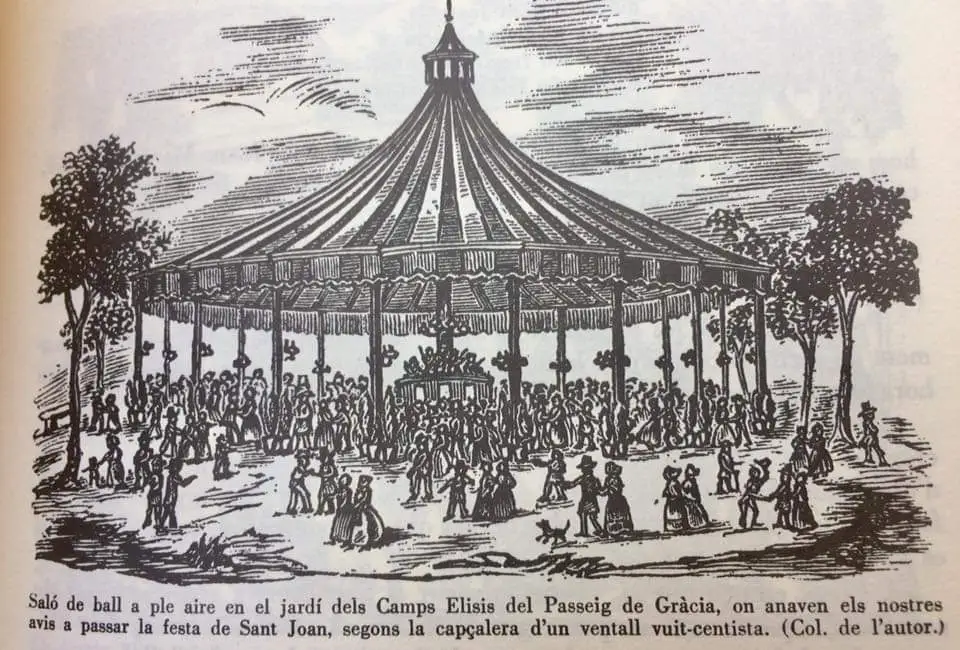

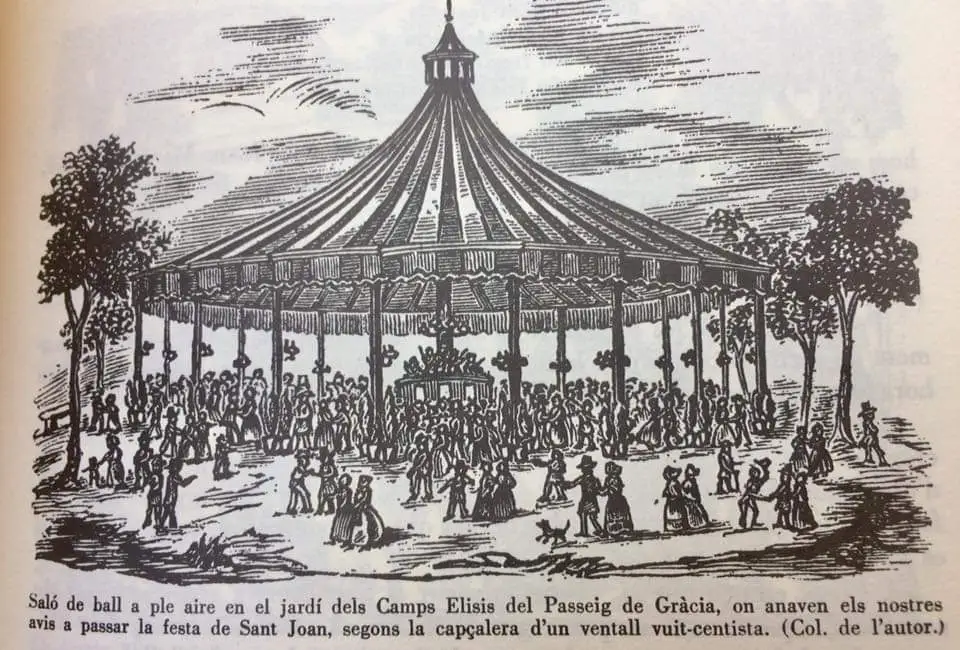

Sant Joan bonfires: light, fire, and communal safety

Sant Joan bonfires act as a communal firewall. Sparks and flame are literal and symbolic tools of safety on a night when herbs and stories feel potent.

Villages trusted light to keep witches away while people danced and tended flames.

House and threshold protections: palm, salt, rosemary, laurel, holy water

A house becomes a small fortress. People placed blessed palm at chimneys and salt, laurel, rosemary, or holy water at windows and keyholes.

These acts show the role of ritual: whether or not one believed in witches, rites taught care, attention to the ground, and a shared script for safety.

“A palm frond above a door can be a quiet promise: we watch the door together.”

| Place | Ritual | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Piedraforca / Beret | Gatherings at crags | Meeting of beings; communal memory |

| Montserrat | Sabbatic dances | Dance, music, and boundary tales |

| Villages | Palm, salt, holy water | Threshold protection and shared care |

Conclusion

I close by picturing a man and a woman standing at a calm pool as dusk slips into light. That quiet scene holds many small stories about vows, patience, and the work of love.

A stolen hair, a lost comb, or a galloping horse can turn a simple choice into a long tale. These legends stay near land and water, asking us to treat place as partner and not backdrop.

I ask you to carry a single story forward. Visit a bridge or a spring with respect. Listen to the local voices and let the world—its beings and its mythology—keep teaching you about life, time, and the small ways light returns.

FAQ

What do I mean by Catalonia folklore and why does it matter?

I mean the living traditions, myths, and legends that grew from the land, mountain, and sea. These stories shape local identity, inform rituals like Sant Joan bonfires, and connect people to elements such as water, fire, and earth. They matter because they help me understand how communities passed meaning, safety practices, and moral lessons from one day to the next.

How did these legends travel through time from word of mouth to the page?

Oral storytelling kept tales alive for centuries; families and village gatherings transmitted motifs about night, day, nymphs, witches, and elemental beings. Later scholars and collectors recorded them in books and journals, preserving variations while allowing wider study and reinterpretation.

Who recorded and preserved these myths that I trace today?

I follow the work of folklorists and ethnographers who documented customs and legends. Joan Amades and the Costumari Català are central figures for collecting accounts of rituals, house protections, and popular beliefs about horses, pools, and mountain spirits.

Why do medieval and modern legends about night, day, and “one day” moments endure?

I find they endure because they address universal fears and hopes—danger at night, transformation at dawn, and decisive “one day” events. These motifs tie individuals to communal memory and to the landscape’s features like ravines, rivers, and thresholds.

What are some iconic legends I revisit and why do they matter?

I revisit tales like the Devil’s Bridge, which speaks to river crossings and cleverness; Comte Arnau, a tormented figure with fiery eyes; and Cocollana, a transformative woman-nymph. They matter because each story explores power, punishment, and the human relationship with elemental forces.

Who are the water nymphs and women of water in these stories?

Women of Water—Dona d’aigua—appear as lovers, guardians, or dangerous charms at gorges and pools like Gorg Negre. I see them as intermediaries between worlds who teach about oaths, consequences, and the life that springs from springs and rivers.

What role do witches play in these tales?

Witches often appear at night combing hair by a pool, summoning storms, or defending community knowledge. I interpret them as custodians of folk medicine, weather lore, and boundary customs—figures who work at the edges of domestic life and the wild world.

How do elemental guardians show up in local mythology?

Elemental guardians manifest as beings of water, earth, air, and fire—protectors of mountains, ravines, and houses. I read these figures as personifications of natural forces that demand respect and ritual, whether through offerings, bonfires, or threshold protections like salt and rosemary.

Why are hair and combs recurring symbols in the stories?

Hair and combs often signal enchantment, vulnerability, and transformation. From three hairs of the devil to combing at the pool, these objects link physical appearance to destiny and the negotiation between human women and supernatural beings.

Which places and rituals should I watch for when studying these tales?

I pay attention to mountains such as Montseny, Pedraforca, and Montserrat, to ravines and river crossings, and to rituals like Sant Joan bonfires. I also observe house protections—palm, salt, rosemary, laurel, and holy water—and seasonal celebrations that anchor stories to lived practice.

How do these myths influence everyday life and safety practices?

The tales often contain practical advice about land use, weather, and personal safety. I find instructions about avoiding dangerous pools, respecting wild horses, or using herbs at thresholds are woven into stories so people learn survival and communal norms through narrative.

Lascia un commento