On my first dawn walk along the Atlantic cliffs, I felt a hush that seemed to keep centuries in its pocket. The light hit a Roman tower and an old hill fort, and I understood how place and past can fuse into an almost cinematic mood.

I open this list with the sites and figures that made me fall for the region’s eerie past. I chose accounts that blend documented history with oral tradition so the picks read like great scenes in movies but remain rooted in archives and maps.

My tour moves from true-crime lore to folk belief, from castros and Roman walls to pilgrim roads. Each selection links people, time, and landscape so the whole feels like a guided walk through layers of the world at Europe’s edge.

Key Takeaways

- I curate places and figures tied to verifiable history and living tradition.

- The picks span archaeological sites, trials, and folk belief for balance.

- This is a personal, guided tour that reads like a compact legend cycle.

- Expect links to pilgrimage routes, Roman remains, and seafaring lore.

- Each entry highlights the people behind the myths, not just the myths.

Why I Keep Returning to Galicia’s Haunted Past

What pulls me back is how the place folds centuries together into a single walk. The layered history shows in small things: carved stones, shrine niches, and petroglyph fields underfoot.

I come for the mix of material sites and lived culture. Camino routes still shape villages and daily rhythms along the Atlantic valleys. That continuity makes old rites feel present in everyday life.

Writers long ago called this region full of superstition, and that label stuck. Yet the real draw is how Roman engineering, medieval devotion, and early modern fear leave tangible marks on the landscape.

I prefer to stand in the place itself rather than trust polished retellings from the wider world or the versions we see in movies. Being there lets me test what the accounts omit and what endures after many years.

- I listen for how songs and speech carry memory.

- I watch how communities explain the unknown with faith and caution.

- Each site teaches a lesson about endurance, routes, or memory.

| Element | What I see | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Petroglyphs | Spirals and carvings on stone | Link to ancient ritual and local memory |

| Camino paths | Villages shaped by pilgrims | Continuous practice that holds community ties |

| Hill forts | Marked ridges and walls | Visible layers of defense and daily life |

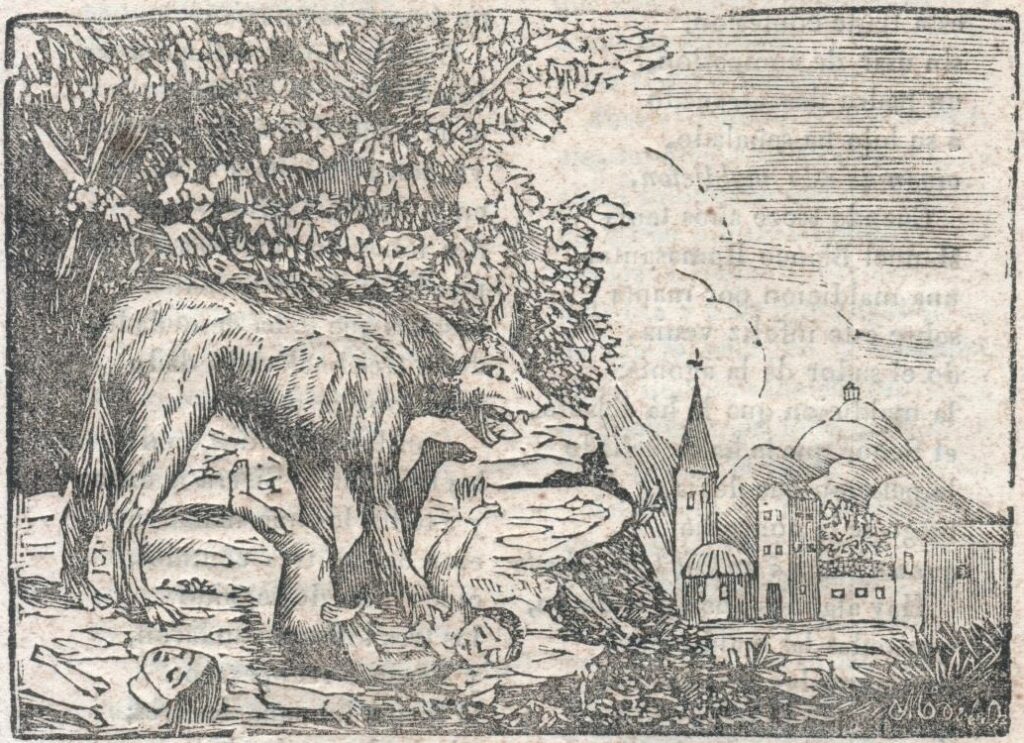

The Werewolf of Allariz: Spain’s First Serial Killer and the Full-Moon Defense

A single trial in Allariz turned a mountain path into the stage for a legend and a legal puzzle. I trace how a string of vanished people became headline grief and courtroom theater.

Confessed murders in the dark forest

At the start of the 19th century, thirteen people disappeared and were later found dead in the forest near Allariz. Manuel Blanco Romasanta confessed to several of the confessed murders. He claimed a family curse made him a werewolf during the full moon.

“I was cursed”: lunar calendar and court testimony

Romasanta arrived at trial carrying a lunar calendar. He said he transformed in the mountains of Couso and hunted with two others. His defense mixed the supernatural with vivid, physical detail.

“I rolled, convulsed, and at the full moon I changed into a beast,” he testified at the trial.

Trial, science, and reputation

The court split its findings: some deaths looked like wolf attacks; others pointed to human crimes. Experts debated clinical lycanthropy versus calculated homicide. The press dubbed him the Tallow Man after rumors he sold clothing and soap from victims’ fat.

| Year | Key fact | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 1809 | Romasanta born in Regueiro | Origins noted in records |

| 1852 | Trial in Allariz | Public debate on defense and science |

| 1853 | Sentence commuted | Study proposed; death in custody |

Galicia’s Witches: From Maria Solina to centuries of meigas and bruxas

A single name—Maria Solina—tethers centuries of rumor to a real fishing town. Her case helps me see how belief, survival, and accusation braided into daily life along the ria.

Maria Solina of Cangas: the woman, the legend, and the Inquisition’s shadow

Maria Solina, born in 1551, was accused by the Inquisition in 1621. She confessed to long-practiced witchcraft said to help people around the Ría de Vigo.

Remarkably, records say she was released. Other accounts claim she died from injuries or returned to her town. That uncertainty is part of the legend that kept her name alive.

Witchcraft, culture, and defense: how people, place, and fear shaped the myths

Commentators from the early modern era often labeled the region a hotbed of sorcery. As Tirso de Molina put it, the area “produces witches as easily as turnips.”

“I have seen how fear of raids and illness turned acts of care into accusations.”

Local words like meiga and bruxa carry meaning today. They reveal how a community used ritual knowledge to heal, protect, and explain the unknown.

- I start with Solina because she links accusation to aid in a tight-knit village.

- Witchcraft accusations often shadowed disputes over property, envy, or illness.

- The persistence of these tales across centuries says as much about cultural memory as about single events.

| Year | Event | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| 1551 | Maria Solina born | Anchors a personal history |

| 1621 | Accused by Inquisition | Shows legal and social pressure |

| After 1621 | Release or death (uncertain) | How myth diverges from record |

Galicia ghost stories you can still feel on the ground

On high granite I trace the marks people left long before maps named the slopes. The places I walk keep active traces: carved panels, ruined walls, and paths that hold the memory of ritual and daily work.

Monte Pindo reads like a stone cathedral. Archaeology shows human activity there since circa 4000 BC, and a 10th-century castle once crowned its ridge. Locals still tell of nocturnal herb gathering and sabbaths; a medieval bishop warned against what he called “pagan lovemaking,” which hints at practices noticed for centuries.

Ancient petroglyphs under Atlantic light

Coastal petroglyphs cluster under the same Atlantic light that sharpens spirals and weapons. Ash samples date many motifs to the early Bronze Age. Craftsmen sketched outlines with quartz tools, then hammered deeper cuts. The spirals, concentric circles, and animal marks link this region to a broader Atlantic world, yet the density here feels distinct.

Torre de San Sadurniño and Viking whispers

I stop at the tower above the ria and imagine lookouts watching northern sails. The tower guarded against Vikings in the 8th–9th centuries. Storms in 2014 washed up anchors nearby, and earth mounds suggest temporary wintering structures like those known from Britain.

“The mountain keeps its counsel: caves, carvings, and a ruined castle that make the granite feel older than maps.”

- I watch tool marks, alignments, and traces of walls to read the place.

- I note how local place-names and craft keep continuity with past culture.

- Where evidence thins, I leave room for myth and for the lived practice of witchcraft lore remembered in songs and names.

| Site | Key evidence | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Monte Pindo | Petroglyphs, castle ruins, nocturnal rites | Long sacred use; activity since 4000 BC |

| Atlantic petroglyphs | Spirals, weapons, quartz tool marks | Early Bronze Age motifs tied to Atlantic exchanges |

| Torre de San Sadurniño | Defensive tower, anchors, nearby mounds | 8th–9th century Viking contact; maritime memory |

Walls That Remember: Lugo’s Roman ring and the weight of centuries

At night the Roman ring reads like a ledger of lives, each stone a short entry in a long record.

The Muralla was built AD 263–276 and still encircles the town for about 2,100 meters. It rises up to 15 meters and wraps roughly 35 hectares.

Walking the Muralla at night: stones, silence, and stories that won’t rest

I walk the circuit at blue hour because the place tightens into its outlines. Towers and gates make the route feel like a spine for markets and gossip.

I look for poured patches and varied masonry. Those repairs read as a ledger of crises and calm across centuries.

- The wall has dozens of original towers and ten gates (five Roman, five from 1853).

- I imagine the people who passed each portal through time.

- Fifty feet of stone above a living town changes how you feel history beneath your feet.

“The ring of stone keeps movement honest; it turns defense into promenade and memory into daily habit.”

| Built | Length | Height |

|---|---|---|

| AD 263–276 | 2,100 m | Up to 15 m |

| Encloses | 35 ha | Dozens of towers |

Today I leave feeling steadied. The wall shows how a town can carry its oldest circle forward and still feel fully alive.

From Pilgrims to “The End of the World”: Camino lore that haunts the coast

A shipping legend and a medieval handbook together gave these coastal paths their long, strange pull. Tradition says a man’s remains drifted ashore after martyrdom, and a ninth-century vision fixed the burial place that would draw people for many years.

By 1140 the Codex Calixtinus mixed miracles with practical notes. The book read like a guide and helped build bridges, hospices, and routes that made this one of the early corridors of the wider world.

St. James arrives by sea: a medieval guide to miracles and mystery

I walk with that history in my pocket. The handbook’s miracle tales did as much to shape culture as its itineraries did to fix distance and time.

Night on the way: villages, moonlit paths, and travelers’ living legends

I favor the thin light of the moon and the hush of villages at night. Small sounds travel farther then, and people trade quiet tales about cliffs, wolves, and safe crossings.

“Every waymarker has been touched by promises and by the hands of women and men who kept lights and doors open.”

- I count bridges and hospices as signs of long use and care.

- I collect local stories not for proof but for how they teach newcomers to move through the place.

- The route feels like a living guide, where legend and history help travelers measure choices against distance and silence.

Spain’s darker mirror: Belchite and Belmez in the wider world of horror

I leave the coastal lanes to look at places where modern violence and strange phenomena force a confrontation between image and fact. In these towns the past refuses tidy closure and the line between spectacle and sorrow feels thin.

Ruins that speak: planes, bombs, and recordings from another time

Belchite stands as a shell of a town leveled in civil conflict and left as a ruin. Visitors and researchers have made numerous recordings there claiming planes, distant bombs, and voices bleed into the silence.

These audio claims show how expectation shapes what people hear. The recordings prompt fights over what counts as evidence and what we bring to a place already marked by crimes and loss.

Faces in Belmez: changing stains, family history, and contested evidence

In Belmez de la Moraleda a concrete floor began showing faces in 1971. For years scientists, journalists, and believers tested the stains’ composition.

Some inquiries tied the phenomenon to a family history: relatives killed in the war, a private grief that reframed the event from novelty into mourning. That shift reminds me movies satisfy appetite for spectacle, yet reality often looks messier.

“Both sites ask what we do with pain when the usual explanations run thin.”

| Site | Noted phenomena | Why it endures |

|---|---|---|

| Belchite | Ruins, claimed recordings of planes and bombs | Public memory, visible wartime scars |

| Belmez (Calle Real 5) | Changing faces on concrete floor | Long investigation, tied to family loss |

| Comparison | Urban ruin vs. domestic site | Both test evidence and how people ritualize grief |

Conclusion

The werewolf case keeps pulling me back. It links court pages to late-night talk and shows how legal records and neighborhood memory shape each other.

My picks share a pattern: people build walls and defenses, then name losses and explain them. Trials, ruins, and roadside shrines all answer the same human need to make sense of crimes and loss.

The tension between science and myth is useful. A medical label or a measured defense does not end a question; it opens lines to family, to community, and to the structures that let a man become accused or hidden.

I carry these accounts like pocket stones. Good movies borrow that mix of testimony, setting, and doubt, which is why the lanes here feel ready for the screen. Walk them yourself and decide what, from these accounts of murders and miracle, you take away today.

FAQ

What draws me to Galicia’s haunted past and why do I return?

I return because the region blends history, culture, and landscape into narratives that feel alive. Old trials, coastal pilgrimages, and rural legends mix with real crimes and recorded events so that myth and evidence sit side by side. I’m fascinated by how towns, walls, and forests preserve memory and create a sense of place that keeps calling me back.

Who was Manuel Blanco Romasanta and why is he called a werewolf?

Romasanta was a 19th-century man from Allariz convicted of multiple murders in northwest Spain. He confessed to killings and claimed a supernatural transformation tied to the lunar cycle, which introduced the famous “full-moon defense.” Medical experts later debated clinical lycanthropy and other illnesses versus calculated crimes, making his case an early intersection of criminal justice and proto-forensic science.

Were Romasanta’s crimes linked to serial killing or to folklore explanations?

The evidence points to serial killings, but folklore and local belief shaped the interpretation. Contemporary newspapers, letters, and court testimony mixed forensic observations with sensational accounts of curses and werewolves. I find it crucial to separate documented crimes, trial records, and cultural myths when studying his story.

What role did trial and medical testimony play in Romasanta’s case?

Trial records include testimony from physicians who examined him and debated causes like hysteria, personality disorder, or a rare psychiatric condition sometimes called clinical lycanthropy. Courts in the 19th century had limited forensic tools, so medical opinion often influenced verdicts and public perception.

Why is Romasanta also associated with the name “Tallow Man”?

Reports from the era mention odd commercial behavior and letters suggesting he sold soap or candles made from fat, which fueled rumors and nicknames. These details blurred lines between grotesque rumor and documented exchanges, and they intensified the macabre image that accompanied his trials and confessions.

Who was Maria Solina and what happened in Cangas during witch trials?

Maria Solina was a woman tried and executed during episodes of witch persecution in 17th-century Galicia. Her case reflects the Inquisition’s reach, local accusations, and social tensions that targeted women as meigas or bruxas. I study her story to understand how fear, gender, and power produced tragic outcomes across centuries.

How did local culture shape beliefs about witchcraft in the region?

People relied on traditional healers, herbalists, and ritual specialists for daily needs. When misfortune struck—illness, crop failure, or unexpected death—communities sometimes blamed suspected witchcraft. I see this as a blend of folk practice, church doctrine, and community defense mechanisms rather than simple superstition.

Where can I experience tangible traces of ancient ritual and myth today?

Sites like Monte Pindo feature caves, carvings, and landscape features associated with pre-Christian rites. Ancient petroglyphs and Bronze Age artifacts dot the coastline, offering direct contact with long human histories. I recommend visiting with a local guide who can explain archaeology alongside oral traditions.

What significance does the Roman Muralla of Lugo hold for night visits?

The Muralla encircles the old town and carries centuries of memory in its stonework. Walking its ramparts after dusk brings a strong sense of continuity—soldiers, pilgrims, and villagers all left traces. For me, the silence between buildings and the weight of masonry evoke stories that history books only hint at.

How does the Camino influence coastal legends and pilgrim lore?

The Camino routes brought diverse travelers, miracles attributed to St. James, and a stream of oral tales. Coastal paths and small villages preserved night-time warnings and miracle stories that merged faith with fear. I find that many modern legends on the coast grew from centuries of travelers’ experiences and shared anxieties.

Why are Belchite and Belmez mentioned alongside Galician tales?

Belchite’s ruined town and Belmez’s famous “faces” are examples of Spain’s broader engagement with ruin, war, and paranormal claims. I compare them to northern sites because they show how ruins, recorded phenomena, and contested evidence feed modern horror culture and influence popular beliefs.

Are the Belmez faces reliable evidence of the supernatural?

The Belmez phenomenon—stains in a house that appeared like faces—sparked scientific, family, and skeptical inquiry. Photographs and records exist, but explanations range from deliberate hoax to chemical reactions or pareidolia. I treat such cases carefully, weighing documented claims against plausible natural causes.

How should I approach visiting sites tied to dark histories and trials?

I advise researching primary sources and choosing respectful, historically minded tours. Many places are still inhabited and shaped by descendants of those involved. Approach with curiosity, respect, and attention to archaeological and archival context rather than seeking sensational thrills.

Can science explain lycanthropy and supposed werewolf cases?

Modern psychiatry recognizes rare syndromes—like clinical lycanthropy—where a person believes they transform. Other explanations include delusion, epilepsy, and toxic exposure. For historical cases, I balance medical hypotheses with trial documents and social context to avoid simplistic supernatural conclusions.

How do I separate myth from documented crime when reading about 19th-century cases?

I cross-check contemporary press reports, court records, and later academic studies. Newspapers often sensationalized events, so legal documents and medical reports offer stronger evidence. I also look at material culture—letters, clothing inventories, and parish records—to build a fuller picture.

Which museums or archives hold the best primary sources on these topics?

Archives like the Archivo Histórico Nacional in Madrid, provincial archives in Pontevedra and Ourense, and local municipal records preserve trial documents, notarial acts, and parish registers. Regional museums often display artifacts and provide contextual exhibitions that I find indispensable.

Are there modern cultural events that keep these legends alive?

Yes. Local festivals, theater productions, and guided night walks celebrate and reinterpret old tales. Pilgrimage routes, reenactments, and heritage projects help communities present history in accessible ways. I see these events as living culture rather than frozen folklore.

How do I responsibly research or write about victims and accused people from the past?

I prioritize archival records, avoid sensationalism, and foreground social and legal context. When discussing accused women or murder victims, I use documented names and evidence while acknowledging the limits of historical sources. Sensitivity to descendants and to the community’s memory matters to me.

What books or authors do I recommend for deeper reading on these themes?

I recommend scholarly works on rural crime and witchcraft in Spain, forensic histories, and regional studies of the northwest. Authors like José Manuel Pedrosa and Carlos Alvarez offer rigorous research, and I complement those with primary source collections and academic journals on Iberian history.

How do I distinguish cultural myth from documented social defense mechanisms like trials and accusations?

I analyze the function of accusations within community life—how fear, illness, and social stress produced scapegoating. Legal records show procedures and punishments, while folklore explains meaning. Combining both perspectives helps me understand why communities acted as they did.

Lascia un commento